I was so ready for AWP in Portland this year: Voodoo Doughnuts! Powell’s Books! Weird-keeping! Even more donuts! But Portland’s quirky appeal was only half of it. I’d been ready since last year’s AWP, when Melissa Wyse of Idlewild Artists Retreat and I cooked up a panel we were so excited to present: “Women Leaders & Entrepreneurs in the Writing Community: Second (Creative) Shifts.” We wanted to open up a conversation about the ways women writers are innovating to sustain their own writing while building and serving their literary communities, and living to tell their tales. We’d assembled a smart, accomplished panel and alerted tons of audacious literary women who could have easily been panelists as well, and asked everyone to invite the people they knew. Weeks before the conference began we felt the momentum of women’s ingenuity and collaborative generosity already carrying us forward like a powerful wave ready to break over the bow of the Oregon Convention Center.

So, you know AWP. The largest annual gathering of writers in the U.S., it’s either a glorious literary smorgasbord or your worst nightmare, depending on who you share an escalator with. Gazing across a crowded auditorium at all the rapt faces locked on a literary giant reading what happens to be your favorite poem, AWP can make you feel like you’ve found your people. Standing in a sloppy bar with your shoes sticking to the gummy floor as the acquaintance you’re chatting with looks through you, watching the door as he mumbles how brilliant your ex-husband’s last book was (the one you bankrolled though you’d already separated, and then he didn’t pay you back or even thank you in the acknowledgments) — in those moments, AWP can make you feel like you’ve just stepped out of your crumpled spaceship onto an airless, empty planet.

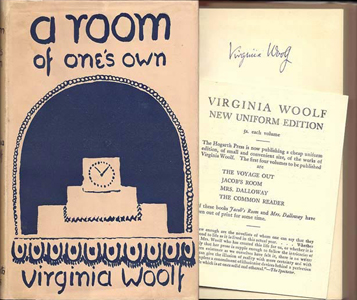

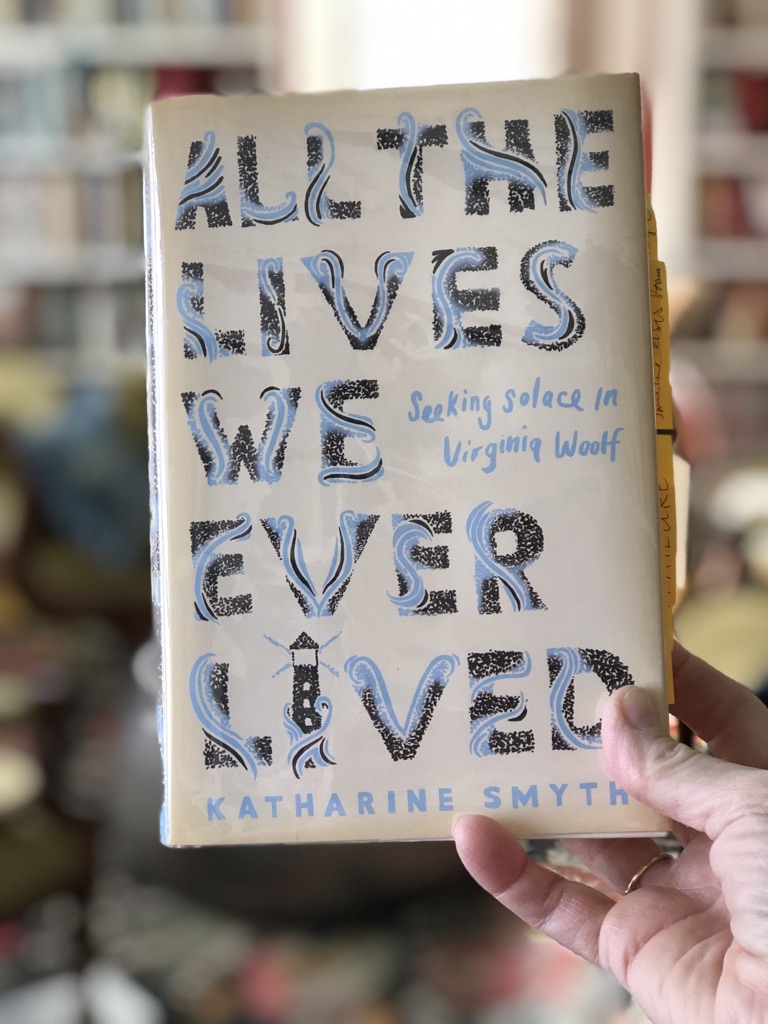

Stick with the panels and the Bookfair, I say, and you can’t help but feel that you’re in the right place. Ego oneupsmanship is not my favorite sport, so I skip the bars and parties and the hoo-hah to attend back-to-back panel discussions with topics like “Alice Munro: We Have No Idea, Either” and “Teaching Novels Inspired by Names Found Scratched Into the Backs of Barnwood Panels,” then finish off with a rushed acquisitive sweep through the Bookfair in the waning hours of Day 3, when everyone is giving stuff away to avoid having to ship it back.

Now that Birds & Muses shares an annual Bookfair table with Craigardan, our partner artists’ organization in the Adirondacks, being ready for AWP means hanging out at the Bookfair most of the time, with the occasional foray to a panel when one of the Birds & Muses or Craigardan writers wants to cover for me at the table (meaning eat candy and plan their next move on the convention floor). I packed a big suitcase full of appealing swag and signage and a little suitcase full of comfortable clothes, homeopathic remedies, the requisite candy, and manuscripts to read during slow periods behind the bookfair display.

And then I tried to get there. And failed. First because of the weather in the Adirondacks. At the end of March it may be spring everywhere else, but it’s the dead of winter where I live. So when I arrived at the ferry across Lake Champlain that would carry me to Vermont and the nearest airport in Burlington, I found that overnight the lake had frozen entirely, closing up the narrow crunchy channel where the ferry had been getting through right up to the day before. I went home and called the airline to rebook my flights while still sitting in my car in front of my house. The next flight I could get was two days later — still okay! I’d get there at lunchtime on opening day of the conference! — but because of the frozen lake, I’d have to drive the long way around the lake to Burlington. For a 6am flight, that meant leaving my house at 2:30am. Still, I was game.

At 3am on the appointed day, just as I crossed the bridge to Vermont, I heard a horrible metallic noise coming from the back of my car, like my car was a banana seat bicycle with a piece of scrap metal stuck between the wheel spokes. In the dark at that hour it was impossible to tell where the noise was coming from. Even the state trooper who passed by and turned back around to help me couldn’t figure it out, but we both thought it was better to head home than to keep going.

So no AWP for me. No reunions with friends and colleagues, no news of the literary universe, no stamp on my passport as a writer-citizen.

Here’s the silver lining. If you’ve ever had a trip or other event cancelled at the last minute like this, you’ll appreciate how it feels: as if you have suddenly been given bonus days. Out of nowhere the gift of time drops into your lap; you can catch up on things, or start things, maybe even do the nothing that you otherwise didn’t have time for. In my case, I had more than plenty of work to catch up on (thanks, concussion!). But I did one other thing that I’ve been wanting to do for a long time: I called Julie Haupert, a writer I met while teaching at the Vortext conference at Hedgebrook. For twenty-three years Julie has had a story working its way out of herself, a story grounded in the memory of working with a severely disabled child incapable of what we think of as the expected means of communication. Whether that experience has anything to do with what happened next might seem unlikely to some, but it doesn’t seem farfetched to me.

Julie is a longtime practitioner of reiki, and had offered to conduct a remote session with me. I loved the idea — receive Julie’s healing energy from afar as she connected to my emotional frequency from 3000 miles away? That had been sounding like heaven from the minute she offered, but I didn’t have time for anything like that! Especially after having a serious concussion in December that’s set me back by months if not years, in every aspect of my life…

Oh…wait a minute. I couldn’t go to AWP. A sudden, five-day deposit in my savings account of life.

So Julie and I got on the phone, me on the east coast and Julie on the west coast, and somehow, honestly knowing very little about me or my private life, she was able to pick up on some radiating energy afloat in the universe that showed her palm trees planted somewhere that palm trees wouldn’t be planted, big red stop signs, a box of fudge, and outside of a gate, a sunny yard, trees in flower, birds flying and calling, a wicker chair…

“I think the palm trees are you,” she said. “Could that be? Are you living somewhere you wouldn’t be planted?”

There are people who will tell you that you can read anything you want into anything you are told. But I would say you should pay attention to what comes to you. Maybe your concussion was the big red stop sign you needed to heed, the box of fudge your reminder that you need to pay attention to the nitpicky directions you’ve been given, but if you follow them you’ll be rewarded. Maybe if you walk through the gate you’ll find the paradise you’ve been needing.

AWP can be a substitute for actually being a writer: it’s a way to prove your membership, to affirm your commitment, to remind yourself that yes, I do belong here even if you haven’t, ahem, been doing as much writing as you’d like to be doing. And that’s okay. We do what we have to do. And other times, AWP can lead you to discover the kinds of things that Julie’s reiki session with me revealed (case in point: the unforgettable panel “Magic and the Intellect” at AWP 2014 in Seattle, with Lucy Corin, Kate Bernheimer, Anna Joy Springer and Rikki Ducornet. That was the answer to why do we do this). But mostly, let’s face it, AWP is an anti-revelation. Every once in a while, though, not being where you are supposed to be is exactly where you are supposed to be. (Thank you Julie for being there with me! ox)

Coming up in a future Musings post: A report from the “Second (Creative) Shifts” panel at AWP 2019. Are you a woman writer who is also a literary entrepreneur or leader invested in your community? Or do you know of one? If so, let me know! As a follow up to our AWP panel, Melissa and I are brainstorming the next step in organizing the energy and experience of this group…Please email me at kate@birdsandmuses.com to find out more.